Science and Meaning

Science and Meaning © 2018

Search For Meaning

Does the universe have meaning? Does it have a purpose or is it ‘driven’ by pure chance? Or should I stop pondering unanswerable questions and just enjoy life? Scientists have divergent views on the significance of the universe. At one end of the spectrum is the iconoclast, Richard Dawkins, who sees a random, indifferent universe with “no design, no purpose…”

At the other end is biologist, Jane Goodall, who believes the universe is a meaningful, purposeful place. In between there are theories ranging from a ‘conscious universe’ to a ‘self-creating universe’. Whatever their beliefs, there’s almost always a shared sense of wonder among scientists.

I’ve always had an intense ‘need to know’. I was religious in my youth; I studied science at university; and when I became a teacher and writer the natural world captured my imagination. Now at 60 plus, I’m looking for connections between everything.

This essay condenses the ideas that have attracted me recently. I acknowledge my debt to greater minds but I take some comfort from Jim Holt’s conclusion (after he interviewed some genius types), that,

No one can confidently claim intellectual superiority in the face of the mystery of existence.

In it’s quest for hard evidence, science can’t assess the meaning of life (it can’t be measured or tested) but there are some fascinating connections to be explored, and science itself can point to some meaning.

The comb of the hive bee is absolutely perfect – Darwin

The universe is astonishing – from spiral galaxies to hexagonal honeycomb – and when I started writing for children, I realised what a gift this was. Imagine a tiny boneless creature that talks by dancing; has a weapon it can only use once; a GPS system using magnetic crystals; and which makes the sweetest syrup on Earth – a side-effect of which is the production of food for humans. I couldn’t make up anything so outrageously enchanting as the honey bee (which became the hero of my first novels).

Several things suggest an underlying meaning in the universe: the laws of nature; the evolution of life; the cause of the universe; and the experience of wonder.

The more I examine the universe and study the details of its architecture, the more evidence I find that the universe in some sense knew we were coming.

– Freeman Dyson, physicist

Sources

A Many-Colored Glass – Freeman Dyson

Why Does The World Exist? – Jim Holt

Laws of Nature

Firstly, the laws of nature show that the universe is a rational place. The laws are mathematical and they seem to be constant throughout the universe. The speed of light is the same everywhere; electromagnetism is a single force; 2+2 equals 4 everywhere (except possibly on the share market). There are four fundamental forces, or constants, which hold everything together: electromagnetism, the weak and strong forces in atoms, and gravity. Even the slightest variation in these and we wouldn’t be here – the constants have exactly the right values to make life possible.

In high-school physics we studied wave interference patterns with our cool, goateed teacher, Mr Scott, who taught us with movies and got me hooked on science. Gazing at the radiating lines where waves ‘interfere’ (collide) with each other and disappear, I was struck for the first time by how orderly the world was; and how mysterious. Of course it helped that I was already in love with the wave patterns from the best television title sequence of the 1960s:

Many scientists think these laws of nature exist for no particular reason – a lucky accident – while others say it’s unlikely that these elegant laws arose by chance. Physicist Paul Davies is cautious about projecting our desire for significance onto the universe but he does conclude that there is meaning at the physical level:

The universe is not arbitrary or absurd, it’s rational, there is a scheme of things.

The entire foundation of scientific thought rests on these logical, mathematical laws and forces – although nobody knows why they exist. The physicist, Eugene Wigner, talked about ‘the unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics’ in science; indeed, some scientists have elevated maths to an absolute Truth; including Heinrich Hertz:

One cannot escape the feeling that these mathematical formulae have an independent existence and an intelligence of their own.

Source

Paul Davies (ABC interview)

Our Cosmic History

How did these well-balanced laws lead to the emergence of life? Consider the sequence of events after the Big Bang that started the universe: matter dominated anti-matter; expansion prevented the universe collapsing; and reactions formed the atoms of life. The ‘Big Bang’ was a name originally intended as mockery. Most scientists had thought the universe had no starting point, then the Big Bang theory proposed a single point of emergence; a beginning. There’s certainly good evidence for it: some of the static you see on an un-tuned TV screen is left-over heat radiation from the Big Bang.

Here’s the theory: the universe began with a sudden expansion almost 13.7 billion years ago. At that time the density required for life to emerge was present to within a millionth of a millionth percent. When the universe expanded it formed atoms of hydrogen and helium first – then the atoms of life (carbon, oxygen etc) were made by stars in finely balanced reactions (which prompted astronomer Fred Hoyle to say, “a superintellect has monkeyed with physics”) .

When stars went supernova the atoms of life were flung out into the universe and began their journey… to you. These exact same atoms of Big Bang and stardust still make up most of your body mass. It’s mind-numbing to try and grasp that this ancient universe is literally ‘me’ – and that my atoms have been recycling through planets, plankton, penguins and people. It’s also oddly reassuring because it suggests connections run deep, as physicist, Marco Bersanelli, so eloquently put it:

Life, our own existence, requires the confluence of the whole history of the universe in order to exist. … life depends on stellar cycles, on the explosions of supernovae, on the rhythm of cosmic expansion, on the contrast of density in the primordial universe, on the structure of physical laws, on the value of the fundamental constants…Our presence in the universe is deeply rooted in this cosmic history.

Photo: The remnants of two ancient supernova explosions, Puppis and Vela. Image courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA

The existence of constants and the story of atoms suggest the universe has allowed the emergence of life . This idea is often described as ‘anthropic’ because it seems to give us humans more prominence than we deserve. But it does seem as though the whole cosmic history has been ‘bio-friendly’:

One of the most significant scientific discoveries of the last generation is that the universe was pregnant with the possibility of human existence from its very start. – Keith Ward

Sources

Wonder and Knowledge – Marco Bersanelli

More Than Matter- Keith Ward

Chance Or Purpose?

The alternative to fine-tuning is that the universe is a result of chance. First option: there is only one Universe and life arose within it by an extremely lucky chance. It’s often called the Brute Fact argument: the universe just exists, no matter how astonishing it is. Second option: there are many universes and the one with life arose by chance; again, lucky for us. The latter is the multiverse theory, currently popular with many scientists. With a multiverse, life is not a remarkable coincidence but an ‘inevitable’ coincidence: a simple analogy is the act of repeatedly tossing a coin – with enough tosses you are certain to get both heads and tails eventually; and so with enough universes, sooner or later you’ll get one with life.

The theory of a chance universe has led some scientists to venture into philosophy and conclude that the universe must also be without meaning. Steven Weinberg says the universe is ‘pointless’ and Stephen Hawking even sees chance as an argument against God:

The multiverse concept can explain the fine-tuning of physical law without the need for a benevolent creator.

It could equally be argued that there has to be a ‘coin-tosser’ to get things started.

At it’s most extreme, the multiverse theory says that every possible version of the laws of physics exist somewhere in an infinite number of universes. But it’s an untestable theory; it still does not explain where the rational laws and universal constants come from; nor why multiple universes exist in the first place.

If the existence of one universe requires an explanation, multiple universes require a much bigger explanation. – Stephen M Barr

In a multiverse, life is the ultimate random accident, pushing the questions of existence further out into a multi-void. Whether the universe initially arose by chance or fine-tuning can”t be proved either way. Although it’s interesting that both the rational laws and random chance are part of evolution and quantum physics – it’s a paradox.

Sources

The Purpose Driven Universe – Bernard Haisch

Life In A Nutshell

Does the universe have a purpose? Living things certainly do. Let’s consider how purposeful creatures evolved from ‘mindless’ matter: life from no life. Science has excelled in revealing the physical details of development. For a start, the material world is incredibly well-organised – biological evolution shows the same fine-tuning as the cosmos. All matter is arranged from extremely small bits to extremely big bits; from inner space to outer space: sub-atomic particles are composed as atoms; atoms are arranged into molecules; molecules into cells; cells into organisms; and so on.

The infinitely small is infinitely large. – Louis Pasteur.

Matter seems solid enough but atoms are mostly empty space inside (this explains that vacant feeling I get in the morning). If you took away the empty space from everyone’s atoms you could fit the entire human race into a walnut. How does life come from empty atoms? There are 92 different kinds of atoms and when they join up they become molecules, held together by electromagnetism. Molecules are lifeless, but life appears when they are arranged into cells – of which you have about 100 trillion in your body – which cooperate to form an organism.

These levels of organisation have evolved over many millions of years to achieve a high level of purposefulness. They are complex enough separately, but when you look at combined cell processes, ‘complex’ is inadequate. The intricacy of body proteins and DNA is staggering – it’s like a micro-metropolis in every cell . Proteins never meant much to me until I learned what they busy are doing inside my cells (view a Havard animation). Digesting, healing, sensing and moving is all done by protein molecules in your cells. There are many thousands of different proteins inside us, including enzymes, hormones, and antibodies. Cells can build these protein molecules exactly when and where we need them.

Ultimately, a single cell, when paired with an appropriate mate, can build an entirely new human being, molecule by molecule. David Goodsell, biologist

Image: A small part of a human cell: the bright blue molecules are ribosomes which make proteins for us.

Illustration by David Goodsell (used with permission).

How can the system of protein building be so accurate? Because of an even deeper level of bodily administration: the twisty strands of DNA found in every living thing on Earth. Here’s a library metaphor: inside each cell in your body is a DNA library which contains the precise instructions to build any protein. DNA has six billion bits of information in each cell, the equivalent of the individual words in a library of books. Using these DNA blueprints, proteins are constructed from smaller molecules called amino acids. Like letters of an alphabet, there are only 20 amino acids, but they can be arranged to create thousands of novel proteins.

And here’s the most practical piece of advice in this essay: don’t rely on all your protein building to happen automatically – cell proteins are made from the food you eat, so chose your diet thoughtfully.

Sources

Our Molecular Nature – David Goodsell

A Bee in a Cathedral – Joel Levy

Mindful Universe

Life then is extraordinary and complex. And this life comes from lifeless atoms. Perhaps the most amazing example of this development is from brain cells to consciousness; from neurons to notions.

If there’s one thing that will cause a sense of wonderment with any scientist it’s how the chemicals in the brain can allow me to say this sentence. – Ed Johnson, biologist

The human brain is made of atoms, molecules, and cells which produce subjective thoughts, but it’s not known how this happens – scientists call consciousness the ‘hard problem.’

How can conscious mind come from mindless molecules? Perhaps that question is wrong. Those brain molecules might not be entirely mindless in the first place. One fascinating theory is that ‘consciousness itself is one of the fundamental building blocks of nature’ (David Chalmers) – and that all matter has some degree of consciousness: ‘a whiff of mentality’, as geneticist Charles Birch described it. The idea isn’t entirely new (consider early animism): the great environmentalist John Muir wrote in 1867,

Plants are credited with but dim and uncertain sensation, and minerals with positively none at all. But why may not even a mineral arrangement of matter be endowed with sensation of a kind that we in our blind exclusive perfection can have no manner of communication with?

If that sounds loopy it’s because we tend to divide matter into inanimate and animate. But in nature there’s not always a tidy dividing line between non-living and living (viruses, for example, don’t fit the definitions). Ferris Jabr describes life as a ‘spectrum of complexity’:

The innumerable atoms that make up everything on the planet continually congregate and disassemble themselves, creating a ceaselessly shifting kaleidoscope of matter.

There’s no neat dividing line separating brain matter and consciousness – they are inextricably entangled. But what if mind is also entwined with all matter in the universe? Several great physicists have entertained the idea of a universal consciousness, or ‘Mindful Universe’, including Einstein, Planck, Heisenberg, and Schrodinger.

Mind, rather than emerging as a late outgrowth in the evolution of life, has existed always as the matrix. – George Wald

As a man who has devoted his whole life to the most clear headed science, to the study of matter, I can tell you: There is no matter as such. All matter originates and exists only by virtue of a force which brings the particle of an atom to vibration and holds this most minute solar system of the atom together. We must assume behind this force the existence of a conscious and intelligent mind. This mind is the matrix of all matter.– Max Planck (1944)

The idea that consciousness is an inevitable part of the evolution of life has grown in acceptance, according to biochemist Christan de Duve:

Biologists today tend to see life and mind as cosmic imperatives, written into the very fabric of the universe, rather than as extraordinarily improbable products of chance.

The idea of a Mindful universe is the alternative to a purely material universe. It’s a possible answer to the question, ‘Does the universe have a purpose?’ Perhaps the intention of the universe is to create conscious life. But as far as science goes there is no way to test this idea of a ‘creator universe’ – it’s a point of belief.

Sources

How Do You Explain Consciousness – David Chalmers

The Island Of Knowledge – Marcelo Gleiser

Man’s Place in the Universe – John Muir

Why Life Does Not Really Exist – Ferris Jabr

Mind In Nature

Science won’t accept the idea of a Mindful Universe until there’s evidence. Fortunately, science is constantly evolving – eg., there’s a shift in biology where there’s increasing interest in the inner lives of creatures. Science often reduces life to its component parts (in order to study them) and that’s sometimes led to a rather mechanical view of living things. Biologist, Rupert Sheldrake, has criticised ‘reductionist’ scientists who say that “plants and animals are mere machines without intent; matter is mindless atoms, consciousness a brain illusion.” Sheldrake is a rebel of sorts; he researches things like collective consciousness and the science of spirituality.

The reductionist viewpoint can be seen in how some scientists have regarded animals in the past – they’ve been reluctant to ascribe feelings or a sense of purpose to living things, perhaps because they’ve been wary of anthropomorphism (giving human characteristics to living things). I experienced this when writing children’s books about honey bees: one editor wanted to remove the suggestion that bees have intentions and memory, and the word ‘sisters’ – in fact, bees are genetically sisters, and have great memories.

In the 1960s, Jane Goodall was criticised by other scientists for saying chimpanzees have emotions. Today the weight of evidence shows she’s right: animal have consciousness, intelligence, and feelings. It’s now generally accepted that humans and animals share many traits – indeed, this confirms what evolution has been telling us all along: that living things are our relatives and that all life is deeply connected (as I write this, there’s new evidence that fish are intelligent, relational creatures.)

Acknowledged as individuals, those sparrows, salamanders and squirrels are not interchangeable parts of a species machine. They are beings with their own inner lives and experiences. Brandon Keim

Plants too are increasingly seen as organisms with their own style of intelligence. Plants have up to 20 senses, including smelling, tasting, and sensing light and sound. The root tips are remarkably intelligent: sensing gravity, water, light, pressure, hardness, volume, nutrients, toxins, microbes, and messages from other plants. For example, forest trees use a ‘wood-wide-web’ of underground fungi through which they deliver food and water to other trees in need, and also signal other trees to warn them about insect attacks.

In the last century, the formerly sharp lines separating humans from animals—our monopolies on language, reason, toolmaking, culture, even self-consciousness—have been blurred, one after another, as science has granted these capabilities to other animals. – Michael Pollan

Sources

Being a Sandpiper – Brandon Keim

The Intelligent Plant – Michael Pollan

The Science Delusion – Rupert Sheldrake

Quantum World

The idea of mindful matter sounds more like metaphysics than science but it nestles nicely alongside quantum physics (the home of weird science) which studies the tiniest particles. The founder of quantum physics, Werner Heisenberg, suggested the smallest parts of matter are more like ‘ideas’ that physical building blocks.

Quantum physics is based on mathematics and it does not translate easily into words – the great physicist, Richard Feynman, said that nobody fully understands it. Consider the paradoxical behaviours of atoms:

Atoms can be in two or more places at once, penetrate impenetrable barriers, and know about each other instantly even when separated. – Marcus Chown

Atoms are small. Picture a walnut in the palm of your hand: if the walnut was an atom then your hand would have to be scaled up to the size of the Earth. Inside atoms, electrons buzz in a kind of ‘cloud of unknowing’ around a nucleus. The quantum world is fuzzy: the smallest particles are not solid like the world we see and touch. They behave as if they were both waves and individual particles – think of a wave in the ocean, made of individual water droplets. Light is the most amazing example of this: it’s both a wave and a particle (called a photon) but you cannot observe them both at the same time.

Atoms exist as a kind of cloud of possibility: for example, scientists can only predict the likelihood of a electron being in a particular spot around an atom. The most extraordinary behaviour of atoms is shown by experiments in which looking at a particle (ie. making a measurement) brings about the particle’s ‘existence’ in the place where you look. It’s called the observer effect. Physicist John Wheeler has even extrapolated the observer effect to the real world, speculating that the observer ‘gives the world the power to come into being.’

All these micro-effects are scientifically proven. It seems the heart of atoms is a random place, and yet, paradoxically, this quantum behaviour is governed by rational laws, and it creates stable matter. While chance is clearly involved (in particles and in evolution) it doesn’t mean the universe is purposeless – rather, the universe seems to have ‘inherent direction’ (Keith Ward).

Consciousness might also be a property of the universe:

Quantum theory states that it is the act of observing an object that causes it to be there. If consciousness is at the heart of quantum physics, that puts it at the heart of everything.

– Bernard Haisch, astrophysicist

Geneticist Charles Birch proposed that all matter has some degree of consciousness. He describes how even humble amoeba show a degree of ‘self-determination’ and purposefulness. Birch believed that

All entities from humans down to quarks are centres of experience.

Remember that the current scientific viewpoint is that matter is not conscious; but taken together, quantum physics and a Mindful Universe suggest there are many more layers of life yet to be uncovered. A century ago, the astrophysicist, Sir James Jeans, wrote that the universe looks more like ‘a great thought than a great machine’. Another prominent idea, String Theory, proposes the universe is not based on particles but on smaller, vibrating filaments – a kind of cosmic symphony.

Sources

Science and Soul – Charles Birch

Quantum Physics – Marcus Chown

The Purpose Driven Universe – Bernard Haisch

The Reason

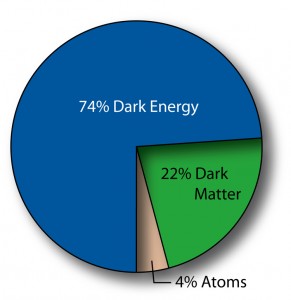

Was there a cause for the universe, or did it appear out of ‘nothingness’? Consider the ingredients of the known universe:

Image credit: NASA/WMAP Science Team

Image credit: NASA/WMAP Science Team

Dark Energy hides in ’empty’ space – scientists don’t yet know what it is, but they do know it’s made the universe expand. Dark Matter particles are also invisible – the evidence of them is that we see stars being pulled by their force. The remaining sliver of the universe pie is Normal Matter; that’s anything made of atoms (potatoes, pigs, people). The universe remains largely mysterious and there are many theories about the cause.

Jim Holt asked some deep thinkers, ‘Why does the universe exist?’ Their answers ranged from optimistic (we will find a reason) to pessimistic (there is no reason, so no need to look). Scientist, Adolf Grunbaum, said the universe is a brute fact because time did not exist before the universe (in other words, there was no ‘before’) so “there is no need to look for a cause, divine or otherwise”.

The philosopher, Leibnitz (1673) was more optimistic:

For every thing there must be a reason for that thing’s existence.

Leibnitz’s Principle of Reason has driven scientific endeavour – it’s the human desire to find out how the world works. It also fits with the mathematician’s credo, ‘where there’s a pattern, there’s a reason’ (Douglas Hofstader); and with the view of some philosophers that ‘nothingness’ is impossible.

The Principle of Reason leads to this conclusion: if the universe exists, then it must have a cause. What is this cause? That’s the biggest unanswered question. Paul Davies suggests that the universe might be its own cause thanks to a kind of feedback loop: its laws, life and consciousness all explain each other through quantum-level events. It’s the ‘creator universe’ idea again. Christian de Duve also favours a self-created universe; but he also proposes an ‘Ultimate Reality’ behind it all:

Science has given us a glimpse of this reality, by revealing the strange objects and concepts… that lie behind entities such as the cosmos, matter, life, and mind.

The exact nature of a ‘Mind’ that exists throughout the universe is open to much speculation. Marcelo Gleiser pictures it as a kind of ‘universal disembodied Mind’ (see 1950s’ sci-fi); or it could be a more diffuse cosmic consciousness; or an intelligent being.

An initial ‘First Cause’ must be something that has always existed (otherwise it would need a cause itself). The main candidates for First Cause are the multiverse and God, both lacking in evidence, but both possible.

Sources

Why Does The World Exist? – Jim Holt

Templeton Foundation – Big Questions

Beyond Science

One definition of God is an ‘eternally creative intelligence’ (Callum Coats). The mathematician, Kurt Godel, believed that consciousness and mathematics could only be explained by such an intelligence (and he devised a formula for God’s existence). Leibnitz believed in ‘a necessary being’ – a cause outside the chain of explanation – a being who made a meaningful universe (or a multiverse). Astrophysicist Bernard Haisch also argues for an infinite, intelligent being’ existing outside space and time…a being who set the universe in motion and left it alone to run on its own laws and evolution. The nature of that Being is another story and one which I’ll dodge for now:

Science and spirituality were not so disconnected in the past. The early church supported scientific development by setting up the first universities, where science was a free-ranging subject called ‘natural philosophy’:

Many of the thinkers we have retroactively dubbed “scientists” freely intermingled their speculation about the natural world with theological, philosophical, and mathematical writings.

– Ian Hutchison

These expansive thinkers included Kepler, Galileo, Newton, Boyle and Faraday. Today, science focuses purely on the material world, but there are still many scientists who embrace both science and some form of spiritual belief. For example, the physicist, Jim Gates, (proponent of a ‘string’-based universe) says that ‘both faith and science are essential’.

Science and spirituality have different aims and methods. Science uses experiments and maths to measure the processes of life; but as primatologist, Jane Goodall, observes:

Science does not have appropriate tools for the dissection of the spirit.

Max Planck suggested that scientists can’t solve the mystery of meaning because we are part of the puzzle itself. Some scientists believe science is all we need to fully explain life – eg. spiritual belief is neurological; love is hormonal; ethics are explained by evolution. A broader view is that knowledge is multi-faceted and can come from many sources. Freeman Dyson talks about the ‘complementarity’ of science and soul knowledge. In physics, complementarity is the existence of two physical realities which cannot be seen simultaneously…eg., light can be modeled as a wave and a particle; you can’t observe them both at the same time, but both models are needed. I think we need more than science to grasp the whole human experience.

Knowledge of grace and beauty, knowledge of ethical and artistic values, knowledge of human nature derived from history… knowledge of the nature of things derived from meditation or from religion, all are sources of knowledge that stand side by side with science. – Freeman Dyson

Science provides measured explanations, and scientific theories are always under revision:

To hope that science will answer all questions is to want to shrink the human spirit, clip its wings, rob it from its multifaceted existence.– Marcelo Gleiser

Gregg Caruso asked 33 scientists and philosophers (from atheists to believers), if science and religion are compatible. There was general agreement that neither science nor religion have all the answers.

Sources

A Reason To Hope – Jane Goodall

The Scientist As Rebel – Freeman Dyson

God’s Philosophers – James Hannam

Science and Religion – Gregg Caruso

Wonder

It’s a sense of wonder that inspires me most of all. The most meaning-saturated moments of my life have been in awe at Nature: a comet at dusk, a taste of honey condensed from the flowers in my neighbourhood, the birth of a child.

Photo: My grandson at 23 hours old.

Wonder about the universe is not limited by one’s beliefs or theories. Even the atheist, Richard Dawkins, has said that “My eyes are constantly wide open to the extraordinary fact of existence.” Of course, feelings of awe and wonder can be explained by a surge in dopamine in the brain. But I hope there’s more to the experience of wonder than that. If a kind of consciousness infuses every particle of matter then a sense of wonder at Nature could be a vital point of connection. Perhaps this is how the ‘soul’ aspects of the universe are revealed to us: by spending time in the natural world. Jane Goodall’s poem, “The Old Wisdom”, speaks about the need to experience Nature to find your soul:

Yes, my child, go out into the world; walk slow

And silent, comprehending all, and by and by

Your soul, the Universe, will know

Itself: the Eternal I.

I like how she associates the soul with the universe (our Big Bang atoms) – and a sense that our lives took billions years to prepare. It’s hard to see the point of a ‘pointless universe’. I feel this most strongly most when writing science for children: I want to convey to them the wonders of the world but also that they have a part to play in it.

To avoid the funk of modern scientific nihilism, we must find joy in what we are able to learn from the world. – Marcelo Gleiser

I’ll always find enjoyment in learning about the wonders of Nature: this week I learned a gecko’s toe-pads are covered in billions of branching bristles which form temporary molecular bonds with surfaces.

When a group of prominent scientists and philosophers were asked ‘Does the universe have a purpose?’, their answers were fairly equally divided between Yes and No. The ‘noes’ said the question is too anthropocentric: there’s no evidence of purpose, and the universe is ‘directionless’. The ‘yeses’ said that the laws of Nature and the existence of Mind suggest a purposeful universe.

Jane Goodall’s book, A Reason To Hope, is one of the best integrations of science and soul I’ve read, perhaps because she has lived out the challenges of being both a scientist and a believer:

We either agree with Macbeth that life is nothing more than a ‘tale told by an idiot’, a purposeless emergence of life-forms…or we believe that, as Teilhard de Chardin put it, ‘There is something afoot in the universe, something that looks like gestation and birth.’

In his book about the limits of science, Marcelo Gleiser concludes that it’s our sense of wonder that often drives scientists: ‘It is awe that fuels us’ he says. And Robert Sapolsky, neuroscientist, writes that:

The purpose of science is not to cure us of our sense of mystery and wonder, but to constantly reinvent and reinvigorate it.

One of the great mysteries is the nature of the universe: it’s a curious mix of elegant structure and underlying randomness. Is this a chance universe or a purposeful one? It can’t be proved either way, so perhaps it’s more about which story you prefer. I prefer a universe where ‘everything belongs’ (Richard Rohr); where life is no accident; where there’s purpose and meaning. As for finding my specific purpose, that’s a lifetime’s work; but I love what the poet, Gerard Manley Hopkins, wrote:

What I do is me: for that I came.

Sources

A Reason To Hope – Jane Goodall

Templeton Foundation Big Questions

Nothing To Be Frightened Of – Julian Barnes

As Kingfishers Catch Fire – Gerard Manley Hopkins