Steig: Life Affirming Books

William Steig, creator of the movie icon Shrek and children’s writer, has been hailed as ‘an idiosyncratic innocent’, and ‘one of the finest cartoonists and creators of children’s books’ (Jonathan Cott). He only began writing and illustrating for children at 60 years of age, but produced many classic books. His stories are often uncompromising in theme and language, but they all celebrate the richness of relationships and nature.

Steig’s creativity was nurtured by his Socialist parents who encouraged their children to be artists:

My parents didn’t want their sons to become labourers because we’d be exploited by businessmen, and they didn’t want us to become businessmen because we’d exploit the labourers.

During the Great Depression he had to get work to support the family, and began work as a cartoonist with the New Yorker magazine in 1930. He clocked up 1600 drawings and 117 covers. John Updike said Steig’s art ‘was drawn as if with the unpremeditated certainty of a child’s crayoning.’

Steig’s first big success was Sylvester and the Magic Pebble (1969), which won the Caldecott Medal. Sylvester the young donkey is randomly trapped inside a boulder while his parents search frantically for him. Steig’s depiction of the police as pigs generated some heat, and the book was briefly banned in a few states.

Magic Pebble is about a child’s fear of separation. It’s Steig’s own version of his personal favourite, Pinocchio, about a real boy trapped inside a piece of wood. Transformations, both magical and personal, would be revisited many times in his books.

The ending is typical Steig: child and parents are reunited in a frenzy of hugging and tears. When he was 15 young William ran away to sea after an argument with his father,:

When I finally got home, my mom and dad hugged and kissed me and we all cried. We were a very emotional family.

Also from 1969, Rotten Island is a less well known Steig masterpiece about a tribe of death-loving monsters on a small island. Their reign of destruction is ended by the arrival of a flower which transforms the island into a paradise. The illustrations are a riot of colour and energy, and Steig’s ugly monsters are the forerunners of Shrek. His rustic drawing style gave his characters a charming, offbeat look.

Steig often covered themes considered unsuited to children’s books. His first full novel – one of my all time favourites– Dominic (1972), touches on death, romantic love, destiny and the nature of good and evil. He uses the animal characters to stand in for adults – as children’s writers sometimes do to appeal to parents. Dominic is a dog with a generous free-spirit, a wanderer who always follows the path of adventure:

Steig often covered themes considered unsuited to children’s books. His first full novel – one of my all time favourites– Dominic (1972), touches on death, romantic love, destiny and the nature of good and evil. He uses the animal characters to stand in for adults – as children’s writers sometimes do to appeal to parents. Dominic is a dog with a generous free-spirit, a wanderer who always follows the path of adventure:

Oh life, I am yours. Whatever it is you want of me, I am ready to give.

says the dog. It’s a marvellous novel (especially read aloud) replete with humour, suspense, rich language and bold characters. The Doomsday Gang for example, are a band of ferrets and weasels who in the end are defeated by ‘the lords of the hitherto silent vegetable kingdom’.

Dominic has been praised as an ‘inspired and inspiring’ classic. It reflects Steig’s creative, sensual outlook on life and only adults will appreciate the deeper themes I suspect. As a youth he wanted to be a beachcomber, traveller, banjo-player, seafarer, or ‘some form of hobo’. His philosophy — ‘life is creation’ — is never far from the surface in his books.

Steig used sophisticated language to entertain rather than befuddle. In the picture book Farmer Palmer’s Wagon Ride (1974), he is at his most playful with words and plot. A farmer-pig suffers hilarious slapstick mishaps as he tries to take gifts home to his family. A rainstorm is described thus,

‘harum-scarum gusts of wind … a drubbing deluge … thunder rambled and rumbled … it dramberamberoomed!’

In Abel’s Island (1976), Steig’s second junior novel, a civilized mouse has to learn to survive in the wilderness. After physical challenges and deprivations, he has a spiritual awakening which helps him remain sane. The story won a Newbery Honour award and has all of Steig’s life-affirming qualities.

He created many picture books with endearing animal characters. The award winning Dr De Soto and The Amazing Bone are among his most popular. Many of his books concern the things that sustain relationships. Caleb and Kate (1977) is about a married couple who ‘love each other, but not every single minute.’ They are separated after a bitter argument and reconciliation comes only after Caleb is turned into a dog and has to live with his wife (as a pet). Who but Steig could make middle-aged characters so appealing in a children’s book.

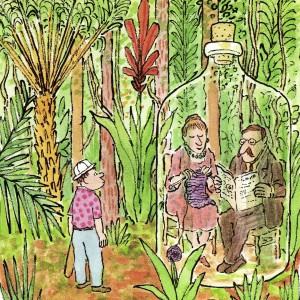

Steig’s exploration of the child’s inner life was also unique. Zabajaba Jungle (1987) explores a child’s imagination with a surreal style of story-telling. A small boy battles through a jungle to free his parents who are trapped in a huge bottle (but don’t know it).

In Spinky Sulks (1988), a boy feels misunderstood by his family and goes into an extreme sulk which only unconditional love can overcome. It’s a masterly exaggeration of a familiar family dynamic.

But it’s the character Shrek (1990) that Steig will inevitably be best remembered for, such is the pervasiveness of movie imagery. The movie sent mixed messages about beauty, while the picture book Shrek simply celebrates ugliness. Steig’s Shrek is a charming anti-hero, ‘full of rabid self-esteem’, foul-smelling and without any cute dimples. He woos his princess thus: ‘Your horny warts, your rosy wens, like slimy bogs and fusty fens, thrill me.’

In the 1990s he illustrated books written by his wife Jeanne. Alpha Beta Chowder (1992) is a funny tongue twisting alphabet. This reminds me what befell my axolotl:

‘Abhorrent axolotl, scat! Unless you’d like to feed my cat,’

His last book was When Everybody Wore a Hat (2003) which is about his immigrant family growing up in the Bronx when Steig was 8 years old. In 1916 ‘boys did not play with girls, kids went to libraries for books, and there was no TV’. It’s a fitting final picture book memoir.

William Steig illustrated many other books. He died aged 95, leaving his books as a gift for children and adults alike.

References

The World of William Steig by Lee Lorenz (Artisan, NY, 1998) is a magnificent biography.

Pipers at the Gates of Dawn by Jonathan Cott (1985) has an in-depth interview.