Shock-headed Peter & other Classics

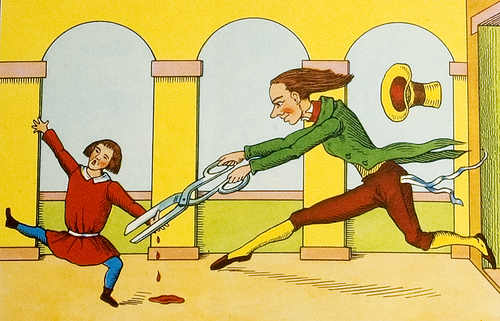

1. Struwwelpeter (1845) by Dr. Heinrich Hoffman poked fun at the dreary moralistic stories of its time and that’s probably why children loved it. (Read the original picture book here).

Struwwelpeter’s ironic subtitle is ‘Pretty Stories and Funny Pictures’ – these are gleefully gruesome rhymes; cautionary tales about disobedience and its consequences; with suitably shocking pictures. Hoffman founded an influential Frankfurt asylum and his patients might have inspired the rhymes.

The most iconic and graphic tale is in The Story of Little Suck-a-Thumb:

Snip! Snap! Snip! the scissors go.

It sounds better in the original ‘klipp und klapp‘ of the German. Watch an animated German version here.

Less well known but just as stunning is the wartime parody Struwwelhitler by Robert and Philip Spence (1941); a sharp satire of the Nazi regime with poems about Hitler and his henchmen (Read more here).

See! the horrid blood drops drip

From each dirty finger tip;

Pie-crust never could be brittler

Than the word of Adolf Hitler.

Look at Bob Staake’s cool modern interpretation of Shock-headed Peter; and read some cautionary rhymes about modern technology (mobile phones, global warming…).

2. The King of the Golden River (1841) by John Ruskin is a children’s morality tale that still speaks loudly today. It’s unique among fairy tales in having a punchy environmental and social message as well as being highly atmospheric. It’s about two brothers who exploit their farmland and have no compassion for their workers:

They shot the blackbirds, because they pecked the fruit; and killed the hedgehogs, lest they should suck the cows; they poisoned the crickets for eating the crumbs in the kitchen; and smothered the cicadas, which used to sing all summer in the lime-trees.

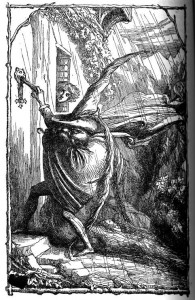

Their fertile valley in Austria becomes a wasteland and is cursed by the Southwest Wind (illustration by Richard Doyle). To break the curse the brothers must take holy water up a mountain to the Golden River, but they fail to help the people they meet on the journey: “The water which has been refused to the cry of the weary and dying is unholy, though it had been blessed by every saint in heaven.” But a third, younger, brother gives the holy water away to needy people and as a result is saved from the fate of his brothers.

Their fertile valley in Austria becomes a wasteland and is cursed by the Southwest Wind (illustration by Richard Doyle). To break the curse the brothers must take holy water up a mountain to the Golden River, but they fail to help the people they meet on the journey: “The water which has been refused to the cry of the weary and dying is unholy, though it had been blessed by every saint in heaven.” But a third, younger, brother gives the holy water away to needy people and as a result is saved from the fate of his brothers.

Ruskin was a Victorian polymath who Tolstoy described as, “one of the most remarkable men… of all countries and times.” Here’s a cool version of his story by the Californian Theater Center.

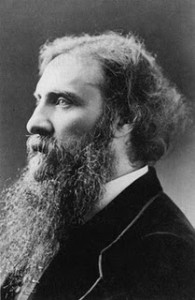

3. The Day Boy and the Night Girl (1879) is a classic fantasy by George MacDonald  about a witch who raises two children in a bizarre experiment: the girl, Nycteris, has never seen the sunlight, and the boy, Photogen, has no knowledge of the night. Of course, the two eventually meet at twilight and help each other overcome their fears of dark and light. It’s a romantic allegory which also subverts fairy tale roles. MacDonald was an unorthodox preacher turned writer whose fantasy fiction inspired Tolkien and Lewis. His other fairy tales are equally fascinating, my favourite being The Light Princess (1864) a playful story about a feisty princess who has lost her gravity: she floats like a helium balloon and can’t take anything seriously – even the prince who gives his life for her.

about a witch who raises two children in a bizarre experiment: the girl, Nycteris, has never seen the sunlight, and the boy, Photogen, has no knowledge of the night. Of course, the two eventually meet at twilight and help each other overcome their fears of dark and light. It’s a romantic allegory which also subverts fairy tale roles. MacDonald was an unorthodox preacher turned writer whose fantasy fiction inspired Tolkien and Lewis. His other fairy tales are equally fascinating, my favourite being The Light Princess (1864) a playful story about a feisty princess who has lost her gravity: she floats like a helium balloon and can’t take anything seriously – even the prince who gives his life for her.

Penguin has published the Complete Fairy Tales…from the intro:

MacDonald’s fairy tales can tantalize us as powerfully as the most enigmatic parables of Kafka or Borges.

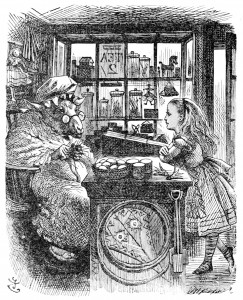

4. Alice in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking Glass (1871) by Lewis Carroll were the first  children’s novels to create a complete fantasy world. The concept challenged the model of children’s literature of its time. Before Alice, children’s books were mostly religious or moralistic. The Alice books are infused with parody of Victorian society, word play, anarchy, and creepy characters courtesy of Tenniel’s illustrations, of which the knitting sheep (left) is my favourite.

children’s novels to create a complete fantasy world. The concept challenged the model of children’s literature of its time. Before Alice, children’s books were mostly religious or moralistic. The Alice books are infused with parody of Victorian society, word play, anarchy, and creepy characters courtesy of Tenniel’s illustrations, of which the knitting sheep (left) is my favourite.

Alice add-ons:

- Lovely hardback version with Zadie Smith’s intro and Mervyn Peake’s pictures.

- Carroll’s revealing biography, Inventing Wonderland by Jackie Wullschlager.

- The Annotated Alice by Martin Gardner is the definitive geek’s guide.

- Salvador Dali’s illustrated Alice is a collaboration of two of the ‘’ultimate explorers of dreams and imagination’. View the paintings.

5. Grimm’s Fairy Tales (1812): One of the appeals of the Grimm fairy stories is how random events interconnect, as A. S. Byatt says in her introduction to The Grimm Reader (online here):

Everything in the tales appears to happen by chance – and this has the strange effect of making it appear that nothing happens by chance, that everything is fated.

I like how the Brothers’ Grimm fairy tale characters meet the forces of their ‘abstract’ world with such courage and cunning. My favourite fairy tale illustrator is Arthur Rackham and a new book of many beautiful Grimm illustrations is here. Some of the original tales are quite gruesome. In Grimm’s Cinderella the sisters slice off their toes to fit into the shoe (modern versions are sanitized).

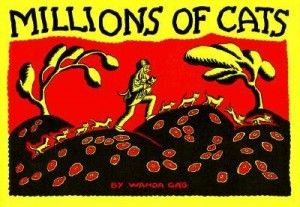

6. Millions of Cats by Wanda G’ag (rhymes with blog). Wanda G’ag (lovely bio here) is one of the finest children’s book illustrators. Her masterpiece is Millions of Cats (1928) the story of a lonely old couple who attract ‘millions and billions and trillions of cats‘. The pictures flow like waves across the pages; clouds, trees, hills and cats all swept along in the flow of story. The black and white gives it that slightly unsettling folktale vibe. As a child I loved the army of cats drinking a pond in seconds, and the final catastrophic catscrap. Try to find her bizarre Nothing At All too, about an invisible dog.

Draw to Live, Live to Draw –Wanda G’ag

7. Ferdinand by Munro Leaf (1936) remains one of the most influential children’s books (it’s never gone out of print) because of its simple but powerful theme. The tale of a bull who likes to smell flowers instead of fighting was seen as a pacifist text at the time of the Spanish Civil War. Ferdinand is an outsider; a free-thinker who bravely chooses to do what he loves instead of following the crowd.

- banned by Franco

- burned by Hitler

- used by Stalin to name a gun

- a favourite of Gandhi

- made into an Oscar-winning movie by Disney

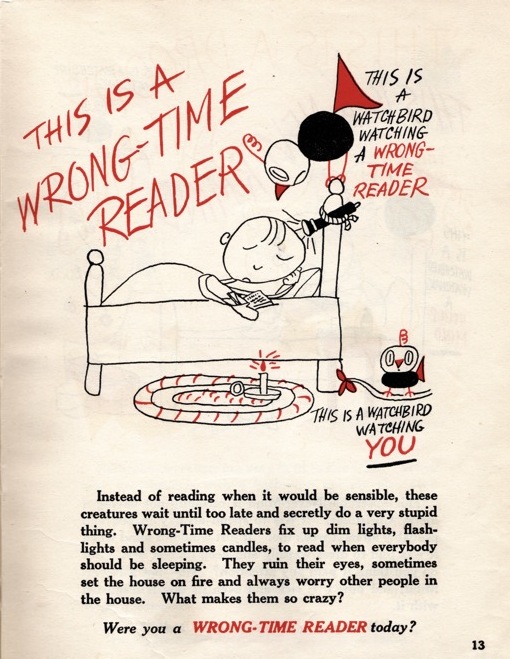

In contrast, Munro Leaf also wrote books which reflected the strict child-raising style of the time. His 3 and 30 Watchbirds (1941) condemns behaviours such as shoe-scuffing, primping, mumbling, moaning, fidgeting, sassing and wasting food. Some of it is in the spirit of war-time frugality but some Watchbirds use some extreme scare-tactics:

Grammar Can Be Fun is slightly more tongue-in-cheek and warns children against slack language such as “gimme, wanna, gonna, and ain’t”.